|

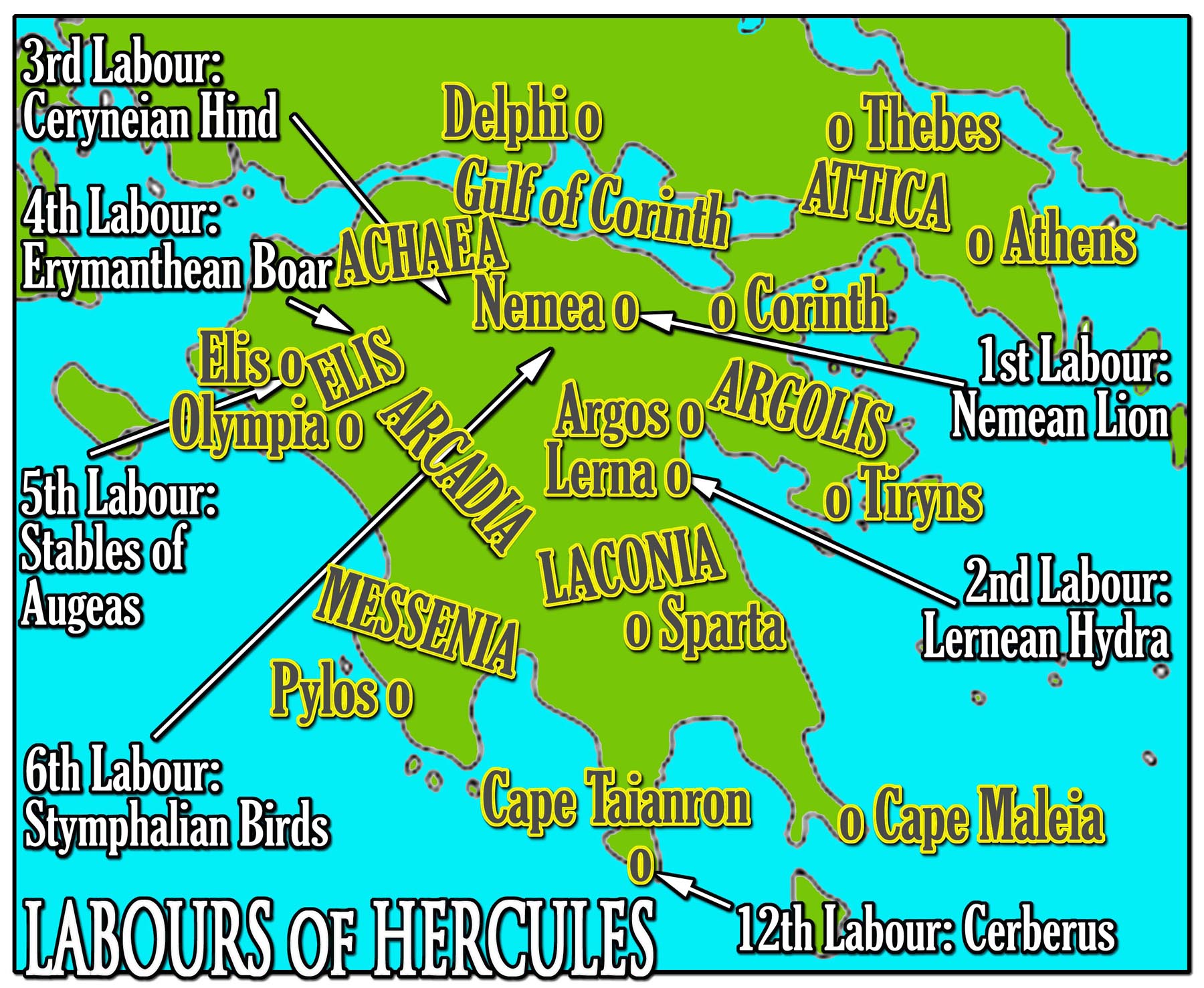

The Sixth Labour: Chasing Off the Stymphalian Birds by I.A. Watson An extract from his novel Labours of Hercules

“What

are you doing out there? Get under cover, you fools!” The shout came from a peasant farmer sheltering in the doorway of a

hero-shrine in the centre of the village. It was the only stone-built

construction in the whole settlement, standing on almost the only completely

dry ground. Hercules

and Iolaus had wondered at the strange design of the huts around the edge of

Lake Stymphala. They’d had to abandon their chariot yesterday, a dozen miles

back, and press across the reed-marsh along marked ridges and goat tracks where

brackish waters occasionally overflowed. The locals, short of firm ground to

build on, had developed stilt-legged shacks with wooden piles driven down into

the water. Long log-bridge roads were roped over the mud. It was an isolated,

inbred corner of Greece and it had strange customs. Like

this one. “Why are you all squashed into that monument?” Hercules wondered. It

seemed as if the entire population of the backward hamlet was packed tight into

the old shrine. Many of them clutched chickens, lambs, and goats. “Quickly!”

warned the farmer. “They’re coming!” “What’s

coming?” Iolaus asked, following the peasant’s frightened line of gaze up into

a bright azure sky. “The

Birds of Ares! Can’t you hear how quiet it’s gone? The animals and other birds

always know when the flock has taken flight.” “Ah,

the Stymphalian Birds,” Hercules approved. “That’s what we’ve come for. I’m

here to get rid of them for you.” “This

is Hercules of Tiryns,” Iolaus explained. “The hero?” “He’ll

be getting funeral orations then, and you with him, if you don’t both get in

here now!” Iolaus

discerned a dark shadow to the north, across the water of the lake. It was like

a coil of smoke but it moved differently, more fluidly. He pointed it out to

Hercules. “They’re

almost upon us!” the farmer called. “Last chance. We have to seal the door.” Iolaus

noticed that the stonework of the old shrine was chipped, as if it had been

struck with daggers or arrow-heads. Most of the other buildings of the village

had small holes in their roofs. The damage most resembled the result of

catapulting scrap iron at an enemy host. “Hercules,

we might want to take cover,” the charioteer admitted. The

hero watched the cloud approach. Nearer, it resolved itself into a vast flock

of black-plumed heron-sized birds. Their beaks and claws glinted metallically

in the sun. “Shields,” called Hercules. Iolaus

dragged Hercules’ medusa-shield from the pack and passed it over. He equipped

his own aspis and readied a shortsword. The

villagers despaired of them and closed the shrine door. Hercules

planted his shield at his feet for when he needed it and nocked an arrow in his

bow. “Let’s see how hard these Birds of Ares are to kill.” His

first shot was at long distance. It arced over the still waters of Stymphala

and dropped a bird from the host. A second and a third arrow felled two more. The

flock numbered in the thousands. “We might need more arrows,” Iolaus breathed. Hercules

used up the whole score of shafts in his quiver and reached for club and shield

before the birds swarmed him. The

avians descended, trilling an unearthly screech as they aimed for Hercules and

Iolaus. The adventurers defended themselves. Hercules whacked a half dozen of

the birds out of the air with a single club stroke. Iolaus cut down another

pair. The

rest tore at their prey with iron talons. Iolaus yelped in pain as a brazen

beak jabbed through his bronze breastplate and drew blood. More stabs followed

from other birds. Hercules

swatted the swarm aside, but he too was bleeding where the lionskin did not

protect him. The birds knew to aim at his eyes and genitals. Iolaus

retreated until the men were back to back, better able to defend against

enemies that could attack from any quarter including the sky above. “We’re not

winning this!” he called to Hercules. “Move

this way,” the son of Zeus called. He swept another brace down with a slice of

his shield and edged towards one of the peasant stilt-huts. “I

don’t think those things can keep them out,” Iolaus warned. “That must be why

everyone’s hiding in the stone monument.” “That’s

not what I want it for.” The

questers were torn and bleeding when they reached the hovel. Iolaus was ripped

up the worst, but Hercules was scratched and bloody too. Ares’ birds had beaks

as hard as chisels and claws sharp as razors. Hercules

discarded his shield and club and grabbed the hut. He roared in rage and ripped

the whole dwelling off its foundation. Iolaus dropped to the floor just in

time. The son of Zeus swung the cabin round and swatted a hundred or more of

the Stymphalian birds out of the air. He dropped the collapsing hut down and

them and stamped them flat. The

flock retreated, taking to the skies where Hercules could not reach them. “We’re

also going to need more huts,” Iolaus suggested. The

birds wheeled round, flexing their wings in odd ways. A shower of jet-black

feathers flew down like darts. Iolaus

yelped and sheltered behind his shield. Even so three of the razor-sharp plumes

buried themselves into his limbs. Hercules was more exposed and took at least a

dozen. “They

can fire their plumage like darts!” Iolaus shouted, although that had just

become obvious. The youngster was dismayed. The birds could remain airborne out

of range of reprisal and shoot the adventurers down with impunity. Hercules

heaved the lad under his arm as if he was a straying sheep and raced full-pelt

into the next cabin. A rattle of arrow-feathers followed them. Some pierced the

wattle-and-daub walls. Others slashed through the fabric roof. But the birds

could no longer see their enemy to aim with such accuracy. Some

swooped down to fly through the doorway. Hercules fended them with his club. Then

the birds revealed another tactic. They began dropping guano around the cabin.

Where it landed on water the swamp turned dark and pestilent. On vegetation the

droppings killed instantly. Ordure began to eat through the fabric of the roof. “I

had less trouble with the Hydra!” Hercules complained. He pushed Iolaus into a

corner, dropped on top on him, and shrouded them both in the Nemean lion-skin,

pulling it over them like a blanket to protect them from the deadly rain of

feathers and droppings. The

birds continued their assault for an hour, but when it became clear that they

could do little more harm they lost interest and swarmed away, cawing their

malice and winding back north to their nests. Hercules

peered out from shelter. The hut was in shreds. Every bit of vegetation for

twenty yards around was blackened and dead. Hundreds of those deadly plumes

were embedded in the ground, already melting into foul pungent goo. “My

lionskin is going to need a wash,” noted the hero. Iolaus

dragged himself from under Hercules’ bulk. “I won’t tell the bards about this

if you don’t,” he promised. Now

the attack was over, the people of the village ventured out of the hero-shrine

again. Iolaus was able to see from the dedication inside that the monument was

to Stymphalus, son of Elatus of Phocis,[i]

for whom the lake and region were named.

Paintings inside the shrine showed the old hero’s death, treacherously

murdered by King Pelops at a peace conference, dismembered and scattered across

Greece; for which Pelops had been punished by the gods. “You’re

alive!” the farmer who had called out to them before gasped in amazement. “How

could you survive the Birds of Ares?” marvelled another. “What

happened to my hut?” asked a third. Hercules

dipped his lionskin into the waters to wash off the scummy droppings that

crusted it. Unhealthy swirls of disease twisted off into the foetid swamp. “Who

can tell me about those birds?” he asked the villagers. The

peasants were reluctant to discuss the avians. They had a superstitious belief

that if they named the birds they might attract them again. Hercules did not

scoff; after all, he avoided naming his dead children. Even then he sometimes

heard them, and once or twice he’d been awoken in the night as tiny hands had

pulled his beard. The

farmer who’d tried to save them passed on directions to the city of Stymphalus

further round the lake, where he claimed there was a temple of Stymphalian

Artemis and Athena that might answer the hero’s questions. Hercules

and Iolaus doctored their wounds and limped on along the marsh tracks. *** “Keep

back!” called out the gatekeeper at the palace of Phalanthus, home of the royal

house of Stymphalus. “I have strict orders not to admit anybody.” “This

isn’t anybody!” Iolaus objected to the porter. “This is the famous Hercules of Tiryns,

whose name is known across all Greece. He is a son of Zeus, the hero who

overcame the Minyans, who sailed as an Argonaut, who cast down Troy. He slew

the Nemean Lion and the Lernaean Hydra and caught the Boar of Mount Erymanthus.

Admittedly he’s not looking his best right now, but that’s all the more reason

to let him in to receive hospitality from your master.” “I’m

sorry,” the gatekeeper apologised, “but I’m really not allowed to let in

anyone. There’s plague in town, sickness and death across the whole district,

spread by those monstrous birds. My master King Phalanthus is away in Tiryns

seeking aid from High King Eurystheus, and his daughters keep his household

now. They have commanded that our gates be sealed, that no pestilence might

enter.” Hercules

was not impressed. “I’ve come a long way – from Tiryns, by request of

that same Eurystheus – and I’ve trudged through far too much swamp and mud to

be denied meal, bath, and bed.” There

was movement inside the courtyard. Several women came to the gate, veiled

against the diseases that infested the town. “Didn’t you hear our orders?” one

demanded. “Go away.” “There’s

no room for you here,” another said. “We

can’t allow you in. Anyone might be infected,” commented a third. “Try

Athena’s precinct,” sneered another. “They’re letting anybody in there, no

matter who or what they are.” “We

don’t even know that you’re who you claim to be. Anyone can call himself

Hercules.” “Well,

I can settle that at least,” growled the hero. He reached out and wrenched the

gate from its hinges, then crumpled the bars until they were knotted in a

tangled ball. The uncourteous Stymphalides screamed and fled. Hercules

bowled the wad of bent metal to crash down their front door, and stamped away.

“Let’s find some other place that will receive us with proper duty,” he shouted

to Iolaus loud enough for both town and palace to hear. “No honour resides

within those walls!”[ii] The

angry hero stormed down to the forum and headed for the temple compound and the

altar of Athena Parthenos. The

young woman in command there also refused them entry. She took one look at the

travellers who limped up to the precinct and sent them out again to wash.

“There’s enough sickness in here without you treading in more,” she scolded.

“Out back is a fountain spring with clear fresh water. Cleanse yourselves and

your clothes before you come back. Anoint yourself with this ointment of

silphium and borage, sovereign against diseases of the skin. Prayers to Apollo,

Panacea, and Hygea wouldn’t hurt either.” From

the votary’s reference to the god of healing and his daughters it was clear

that there was sickness in the compound. She obviously believed it to be

related to the Stymphalian bird’s ordure; why else would she require anyone to

wash before going amongst the sick? Hercules

and Iolaus did as instructed, stripping to the skin, washing even the bandages

from their encounter with the evil birds. “That was an unusual priestess,”

Hercules observed as he scrubbed. “She wasn’t wearing the usual fancy raiment

of Athena’s servants – though the last one I met was an old woman and didn’t

have the legs and figure to get away with a tiny tabard like this one does.” He

had a very clear image in his mind of the maiden’s short white chiton and loose

head-scarf. “I

don’t know if she was a priestess,” Iolaus considered, “but don’t sleep with

her until we find out.” “I’m

a lay votary of Athena,” the woman answered when asked for clarification as the

travellers returned to the gates. “It’s supposed to be an honorary duty.

I turn up every month and help out with the sacrifices, go in procession when

we do the rites, that sort of thing. But the priestess of the Wise One was

amongst the first to catch the plague, and Athena’s temple servant went last

week. A lot of people have fled, including most of the priesthood, so there’s

really only me to organise things and to care for anybody in the city who gets

sick.” “Who

are you, then?” Hercules asked. “When you’re not deputing for the goddess of

wisdom.” The

votary looked the hero up and down. He’d not yet bothered to put on his wet

lionskin or anything else. “When I’m not deputing for the chaste goddess

of wisdom I am Parthenope,[iii]

a daughter of the royal house of Stymphalus.” “You’re

kin to those harridans who wouldn’t give us hospitality,” Iolaus accused. “I

am giving sanctuary to anyone who needs it here at the forecourt of the gods.” “And

you are maintaining this hospital because nobody else will.” “Yes.

Because Athena is merciful. And to annoy my sisters at the palace, who say I’m

bringing them into disrepute by getting my hands soiled, harming their chances

of good matches. But mostly the Athena thing, honestly.” Parthenope

took them into the temple square. The largest foundation here was to Artemis,

for this was a region dominated by hunting game and fowl, but there were

smaller altars to Apollo and Athena and another hero-shrine to the founder of

the city, dismembered Stymphalus. The forecourt precinct was half-full of ill

people on straw pallets, sheltered from the sun by linen sheet tents. “That’s

a lot of sick people to look after,” Iolaus observed. “Not

really,” Parthenope sighed. “There were more before, but most of them died. I

can’t really heal anyone. I just keep them watered and washed, and try to cram

food down them if they can manage it. A few recover. The Birds of Ares bring

the pestilences of war – dysentery, malaria, that kind of thing. Their

droppings are toxic.” “We’d

noticed that,” responded Hercules “We were hoping there’d be someone here who

could tell us more about the monsters. And how to stop them.” “Well,

I can tell you where they came from,” the votary of Athena offered. “Last

winter was particularly hard at Wolves Ravine on the Orchomenan Road. The

starving wolves began to prey upon animals and birds that they would never have

bothered in less terrible weather, so food became very scarce in that region.

They howled all the time. What with the cold and the game shortage and the

constant wolf-pack noise, the strange birds of Ares who lived in the ravine

abandoned their nesting sites. They all flew off to find somewhere better to

perch and never returned.” “And

they came here, to the Stymphalian Marsh,” reasoned Iolaus. “Yes.

A hot, sticky place, full of fat buzzing insects and huge lazy frogs would make

normal birds content to live peacefully, with plenty to eat and not many humans

to disturb them. But the birds of Ares are not normal birds.” “We

noticed that when we had an encounter with them,” Iolaus said ruefully. “How

did they become so numerous and so deadly?” Hercules wanted to know. “You

are Hercules, a son of Zeus? They say you had to track down the Ceryneian Hind

as your third Labour for Eurystheus of Tiryns. That Hind was the special pet of

Artemis the Huntress, and like her it is swift and beautiful.” Parthenope

pointed to the carving of the divine twelve, the sacred family of Olympians.

She tapped her finger on the engraving of grim Ares, god of war. “Ares’ pets

are like him too, but because he is terrible and warlike so are his

dagger-feathered Birds.” “I’m

taking a dislike to Mars,”[iv]

grumbled the hero. Parthenope

gave him an un-Athenalike wink. “I picture brooding Ares – probably sulking

because Hephaestus caught him with Aphrodite and put a stop to that mischief[v]

- squatting there on his bleak hill Areopagus, a little way off from Olympus

Mons so he can’t quarrel with his neighbours, feeding up his monstrous black

birds and breeding them until they could blot out the sun. And then sending

them to trouble mortals.” “There

do seem to be rather a lot of them,” Iolaus conceded. “Killing them

individually isn’t a problem. Killing them collectively…” “I’m

not even allowed to have Iolaus here help me, really,” Hercules grumbled. “Last

time he did I got disqualified.” “Nobody

could kill all of them,” judged Parthenope. “They are brazen-beaked, brazen

clawed, and brazen winged. Pestilence follows in their shadow. Their poisonous

droppings wither the crops. They fly over flocks of sheep and drop metal

feathers on them to kill the poor animals to carry off and eat. Oh, and they

feast on men as well. What was your task, exactly?” “The

Dung-man said we have to get rid of them,” Hercules recalled. “That’s

not the same as killing them, is it?” Athena’s votary noted. The

hero agreed that it wasn’t. “Are you going to call upon your goddess’ wisdom to

help me overcome the monsters?” “Let’s

assume I am. So the first problem is that you can’t actually get to them. They

nest on the Isle of Ares out there in the middle of the lake – except it’s

really a marsh. The ground is even worse to walk on than the Lernaean Swamp

where you fought the Hydra. It’s too runny to tread on and too solid to row a

boat over. The next problem is the birds themselves. There are thousands, huge

smelly things shaped like giant spoon-bills. And the last problem is that they

can attack from the sky. You have one bow to shoot them. Meanwhile a thousand

of them can launch their plumes at you.” “I

call it cheating,” Hercules grumped. Parthenope

nodded sympathetically. “I’d say somebody at Eurystheus’ palace is getting

clever. Probably Queen Antimache, she’s the brains there. You’ve destroyed

every monster they’ve thrown you at and caught even the hardest-to-find of

creatures. This time they think they’ve found you a challenge that all your

immense strength and stamina cannot solve.” “So

what do I do?” Parthenope

held up a cautionary finger. “Hold on there, hero. My patroness Pallas Athena

has been helping you ever since you set out on these quests. Before you ask her

for more favours, shouldn’t you be paying one back?” “Would

it help if I went up to the palace here and wiped out those inhospitable

Stymphalides?” Hercules offered. “Tempting,”

the votary considered, “but that would be a favour for me, not the goddess.” “Would

it help if I was to make love to you?” the hero offered. “You’re not an actual

priestess of chaste Athena, are you, so there’s no taboo or offence.” “I

doubt that would help me concentrate,” Parthenope pointed out. “Let me think

about the problem for a while, maybe pray and make a little sacrifice. I feel

an idea coming. It just needs a while to be born.” She turned to go and added,

“Born like Athena. Without sex.”[vi] *** Hercules

and Iolaus woke with the sun the next morning, but Parthenope was up before

them, tending to the sick outside the sanctuary of the gods. Hercules watched

her for a while, admiring both her form and her actions. She waved at him but

carried on with her duties. A short while later she vanished into the temple to

conduct what morning devotions she could manage in the absence of a priest or

priestess. “Has

she had an idea yet?” Iolaus enquired. “I’ll

ask her when she comes out,” Hercules promised. Only

Parthenope didn’t come out. Athena did. Hercules

blinked in astonishment at the white-gowned presence with the owl on her shoulder.

It looked a little like the daughter of the house of Stymphalus, but… “Well

met, son of Zeus,” said the goddess. “You have grown since we first encountered

each other.” “Yes.

Thank you for that trick with Hera’s milk, by the way. I finally got told about

it by a centaur who listened to Cheiron.” “Your

father has some plans for you, Hercules.” Athena warned. “And not just him.

Never mind that for now, though,” she advised. “You owe me a favour for my help

with the Lernaean Hydra.” Hercules

admitted that this was the case, even if Hera had added an extra monster in

because Athena had tried to interfere. “What do you want me to do?” he asked. Athena

opened her hands and showed Hercules a pair of strange devices. “These were a

present to me from Hephaestus, smith of the gods,” she explained. “They were

amongst the things plundered by Stymphalus’ son Agamedes from the treasury of

King Hyreias.[vii] They were

dedicated at my altar here when Agamedes’ head was returned for his funeral.” Hercules

looked at the twin items. Each was a set of two concave brazen clappers almost

the length of his palm. A loop-cord allowed fingers or thumb to hinge the cups

open. It was one of the strangest devices he had ever seen. “What is it?” “They

are called castanets, a sort of musical instrument. Perhaps you could play me a

tune on them?” “I’m

trained with a lyre in the classical manner and I can manage a tune with a

syrinx. Wouldn’t you prefer that?” “No.

Try these.” The

goddess had commanded. The hero had never even seen castanets before but he did

not want to let Athena down. He slipped the objects on to his hands and tried

an experimental clack. A deep crash like thunder echoed round the temple court.

Hercules tried for a rhythm but only managed a cacophony. These

were no ordinary castanets, to make a snapping sound between finger and thumb.

These instruments were made by the smith-god himself, and were much bigger and

noisier. As the hero tried to play them they made the most appalling booming

noise. “Like someone dropping a big bag of pans down a staircase,” as Iolaus

put it. “Oh

dear, oh dear!” remarked Athena. “I think you’d better go and to get some

practise. Go out of the city, down to the water’s edge. Learn the instrument

there.” “It

won’t do any good,” yelled Iolaus over the chaos. “They’ll hear this noise all

across the lake!” “Down

to Stymphala, Hercules, and keep trying,” the goddess instructed. “And

then will you help me with these birds?” asked the son of Zeus. “Ask

me again when you have had a chance to improve.” Athena flexed her shoulder.

The huge owl winged into the air, fluttering tawny feathers, and circled round

under the lintel of the Wise Goddess’ temple. Parthenope blinked and shuddered

and was herself again. Iolaus

and Hercules looked hard at the votary and tried to determine how they had ever

mistaken her for Athena; yet the impression had been so strong. “I’m

so glad I’m not a dedicated priestess,” the princess of Stymphalus

confessed. “Getting too close to the gods is not a comfortable experience.” Hercules

was a little bit put out that the goddess should expect him to waste his time

on such a trivial thing as playing these castanets when he had important work

to do in the Stymphalian Marsh. “Maybe we can work something out ourselves?” he

suggested. “I can practise this thing with these clackers later.” “Is

it a good idea to ignore a personal request from divine Athena?” Iolaus

cautioned. “Maybe

it’s a test?” Parthenope suggested. “If you do well with your castanets then

she might reward you with what you hope for.” Hercules

looked at the curious brazen hemispheres in his hands - and realised what was

going on. “Last time Athena tried to help me, Hera made my Labour more

difficult,” he muttered. “But Athena is wise. She’s trying to aid me without

seeming to.” Once

Hercules had that thought, he realised that Athena had wanted him to have the

castanets for some reason. Suddenly he knew how to get rid of the ghastly birds

of Ares. “Of course!” he roared, laughing boisterously. “To the marsh! I can

beat these birds now!” Hercules

strode out beyond the city, into the pestilent swamp that now encroached on it.

Iolaus trailed after him, ignorant of what Hercules was planning so that no

winged spite of Hera’s might overhear and thwart the plan. Parthenope remained

at the sanctuary of Artemis to tend to the sick in her care. The

son of Zeus ventured as far as he dared into the edge of the lake without

sinking too deep into the sucking mud. He gestured for his charioteer to get

well back. “I can’t have any aid now, or that Dung-man will cheat me out of

another Labour. Take cover under the trees so Ares’ pets don’t spot you. Wrap

your ears with something.” Hercules

cracked his fingers, limbered them, then pulled on the castanets. “Ho,

birdies!” he shouted, “Let’s see how you like my music!” His

challenge echoed over the green waters to the Isle of Ares where the

metal-fletched birds now nested. A few of them flew out to see what the roaring

was about. More followed after them, circling high until they saw the hero

wading in the shallows. They swooped down, nearing to launch their

feather-darts. Hercules

started to play the castanets. Only a hero as strong as he could have used

these particular instruments properly, but he made a noise even worse than his

last attempt. It was as if someone was playing skittles with bronze pithoi[viii]

that were filled with old knives and spoons. It was so loud that people heard

it for a hundred miles. The

flock burst into the air, milling about, hammered by the vibrations of

Hercules’ concert. Some of them darted in towards the hero, but each new racket

disturbed them worse, tangling them together to drop into the lake below. Some

scattered, while the rest flew overhead in a group so big that midday was

darkened to twilight. And

Hercules clacked the castanets, booming like a thunderstorm on Olympus,

clashing like the rage of armies. Hercules played for hours. The

Stymphalian Birds were terrified. The howling at Wolves Ravine had been enough

before to shift them from their old nesting cliffs. The sounds Hercules were

making were worse, and much louder. Each new boom sent ripples across the

surface of Lake Stymphala, setting the reeds swaying on the opposite bank.

Every time there was a steady rhythm the hero changed again, driving the avians

to distraction. By

some secret signal, the flock all flew up in the high air, screeching. Hercules

played louder still, straining with all his might to wring horrors from

Hephaestus’ percussion tools. With

one accord, the brazen-beaked murder turned north and winged away, driven off

by the impossible din. They all flew the long distance to the Sea of Corinth

and vanished to the west, never to return. It

was later told that the Argonauts met some birds of Ares while on their distant

journey, but whether they were the same ones from the Stymphalian Marsh or not

there was no way of knowing.[ix]

Other reports of the birds came from the deserts of Africa later on, so perhaps

that was where they ended up. “I

did it, Iolaus!” Hercules called joyfully, setting the castanets aside. “What

was that?” his companion replied. His ears were stuffed with wax. *** “The

sickness will pass away now,” Parthenope assured Hercules when he returned the

castanets to the altar of Pallas Athena. “The first signs of it are already

showing. Some of the children grow stronger, their fevers broken. And my

sisters have dared poke their noses out of the palace, to find that nobody will

speak to them. All of Stymphalus is pretending they do not exist.” “Are

you going to be the goddess again at all?” Hercules asked the votary. She was

back in her brief chiton, not robed as her divine patron. “I

hope not. Once is enough for anybody.” Parthenope looked around for Iolaus.

“Where’s your friend?” “He’s

gone back for the chariot. We couldn’t drag it along all the back roads but

there’s a proper track to your city. He’ll be back in two or three days, which

will give me plenty of time to collect my hero’s fee from the House of

Phalanthus.” “My

father is away,” Parthenope pointed out. “Besides, didn’t I hear that your

stable-cleansing exploit was discounted because Augeus paid you?” “He

hasn’t paid me yet,” groused Hercules. “Still, you make a good point.” “I

think I see an answer,” the votary told him. “Wait here.” She patted him on the

cheek and hastened to Athena’s altar. A while later she attended Artemis’

sanctuary also. A

tentative priest turned up that afternoon, having heard that Ares’ monsters had

been cleared away and the pestilence was passing. He was wandering around the

precinct tutting at all the things that hadn’t been done. Hercules pointed out

scathingly that if all the holy men had not run away then they’d have nothing

to complain about. It

was almost evening by the time Parthenope returned. “Come with me, Hercules,”

she commanded. She led the hero through the city and out by a private gate,

down quiet steps to the lake’s edge. There was a peaceful glade where cicadas

leaned down to make a private bower. The red sun reflected on the waters,

turning them as crimson as blood. “Pretty,”

admitted the hero. “I

may have found a solution to the problem of your hero’s fee,” Parthenope told

him. “You are owed much for saving our land. It’s not fair that you depart

unrewarded because of my family’s meanness or King Eurystheus’ cavilling.” “Honestly,

I’m used to it by now,” sighed the son of Zeus. “Not

this time, generous Hercules. There was a simple answer when I thought about

it. Four knots, that’s proper payment. Who could object to you getting

compensated with mere bits of thread?” “Four

knots?” Hercules was puzzled. “I

have a problem too,” the maiden went on in soft, low tones; her name meant

‘virgin’s voice’. “I’m very honoured to have hosted Athena; or to been her

chariot or whatever happened this morning. Of course I am. But I don’t ever want

it to happen again. So now that the professional priests and priestesses are

returning and the sick are recovering it’s time that I retired. I’ve made my

sacrifices to Athena in the proper form and left her service in amity and

honour. And then I made a nameless offering to virgin Artemis too, as all

maidens must before they leave her care.” “Ah.”

Now she had Hercules’ full attention. Four

knots: two at her chiton’s waist, two more holding it in place at the

shoulders. A flutter of two lengths of gauze, and beneath them a hero’s reward. “Athena

would never manifest through any but a virgin,” Hercules understood. “My

father owes you a royal price,” Parthenope declared. “And

of all things in Stymphalus, you are the most royal.” “Perhaps,

noble Hercules. Until your son is born.” And

so after the clamour of war came love.[x]  |